a particularly relevant quote from Andrew Wiles (the Fermat's theorem dude)

Perhaps I can best describe my experience of doing mathematics in terms of a journey through a dark unexplored mansion. You enter the first room of the mansion and it’s completely dark. You stumble around bumping into the furniture, but gradually you learn where each piece of furniture is. Finally, after six months or so, you find the light switch, you turn it on, and suddenly it’s all illuminated.

I posted last month about resolving some issues in getting plotting and stuff working with AUTO-07p.. it's mostly a series of hacks and workarounds, which, all told is rather unsatisfactory.

It's also pretty clear that I'm not the only one to have bumped up against some of these edges. @mbgrw has a nice post here, which goes into some of it, the key point being:

I generally found it hard to grasp what data structure the AUTO output had been saved in and how to plot the resultant continuation branches and bifurcation points in precisely the way I wanted.

but wait, surely this stuff is documented somewhere?!

anyway, long story short, I (with lots of help) found (at least for me) a really nice workflow..

one of my biggest gripes with AUTO is that I end up with a hundred and one files lying scattered around the place, all the c.whatever files with the parameters specifying what type of continuation I'm going to be doing etc etc.. this is a nightmare to manage, and also, when you're jumping around between lots of files you (or at least I) tend to lose my train of thought, and get distracted..

the basic notion is that these can be replaced by a single python file and a standard AUTO equation file... in the python file we import auto, and work from there..

yam.py

import auto as a sysname = "yam" unames = dict( enumerate( ["i1", "i2", "ng", "nq"], start=1) ) parnames = dict( enumerate( ["invT", "p", "delta","j" ], start=1) ) Ngthr= 2.174757281553398 #constant we might use later print('running r1:') r1 = a.run( e = sysname, unames = unames, parnames = parnames, NDIM= len(unames), IPS = -2, IRS = 0, ILP = 0, ICP = [14], NTST= 1, NCOL= 4, IAD = 3, ISP = 0, ISW = 1, IPLT= 0, NBC= 0, NINT= 0, NMX= 10000, NPR= 1000, MXBF= 0, IID = 2, ITMX= 8, ITNW= 7, NWTN= 3, JAC= 0, EPSL= 1e-07, EPSU = 1e-07, EPSS =0.0001, DS = 0.01, DSMIN= 0.0001, DSMAX= 0.1, IADS= 2, NPAR = len(parnames), THL = {}, THU = {}, ) print('running r2:') r2 = a.run( r1('EP2'), NDIM= len(unames) , IPS = 1, IRS = 0, ILP = 1, ICP = ['p'], NTST= 1, NCOL= 4, IAD = 3, ISP = 2, ISW = 1, IPLT= 0, NBC= 0, NINT= 0, NMX= 50000, NPR= 5000, MXBF= 0, IID = 2, ITMX= 8, ITNW= 5, NWTN= 3, JAC= 0, EPSL= 1e-06, EPSU = 1e-06, EPSS =0.0001, DS = -0.001, DSMIN= 1e-04, DSMAX= 0.01, IADS= 1, NPAR = len(parnames), THL = {}, THU = {}, UZR = {'-p':16.5} )

now, the next part is the nice bit.. instead of calling auto -i, to get the

interactive AUTO pythonic interface, we do

~/ $ PYTHONPATH=~/auto/07p/python ipython

which of course drops us to a standard ipython shell, but, as a bonus, we can

run our .py script, and have the full power of AUTO and ipython available,

without having to overwrite all the nice stuff in our namespace..

now, from within the ipython shell, we can do

In [1]: run yam.py

and so on.. if we wanted to plot something using the normal AUTO interface we can do

In [2]: a.plot(r2, stability=True, use_labels=False, bifurcation_y="i1")

or whatever.. however, what we can also do, is use the standard matplotlib

plotting interface, which for the purposes of comparison with numerically

integrated data, or if preparing for publication is far more useful... by doing

In [3]: from pylab import * In [4]: plot(random_file[:,0], random_file[:,1], '.') In [5]: plot(r2["p"], r2["i1"])

here, r2 is a continuation done by AUTO, while random_file is somewhat

unsurprisingly, a random file.. this is more or less mission accomplished as

far as I'm concerned.. r2["p"] is a numpy.ndarray, which of course can be

scaled, or manipulated as we see fit (another advantage over messing with the

standard AUTO interface)

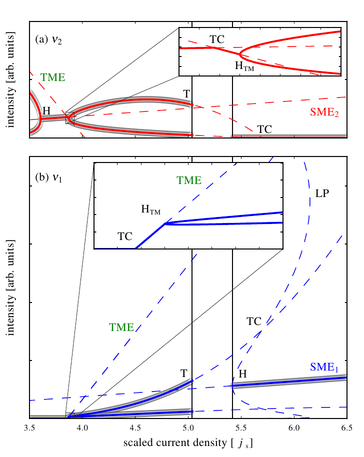

stability?!

easily getting dashed/solid lines for stable/unstable curves is one of the things we lose when we move to plotting in plain maplotlib.. fortunately though, there's a few easyish ways around it.. some examples here, thanks to @mszepien for the generator based suggestions.. (though it doesn't really make much difference which version you use)